![A Firebird crew member holds a delicate coral inadvertently broken off by our anchor chain during our passage from Bali, Indonesia, to the Cocos [Keeling] Islands, January 1977. With today’s warmer, more acidic ocean waters in the South Seas, it’s been difficult to spot vibrant coral like this during the Double X journey.](https://drsamsblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/5_13-rtc_small.jpg)

An eye-opening experience

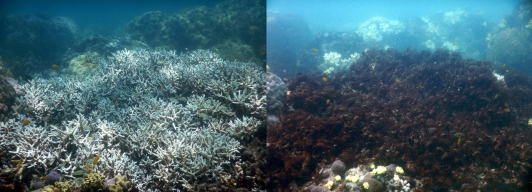

On one occasion, while diving off a glorious motu on Tahaa, Francesca and I came across a beautiful structure descending well below the motu, at least 100 feet down. As we explored, we were astonished to see that most of the coral was bleached or dead. I talked with the owner of the motu about the situation, and he explained that 30 or 40 years ago you could see the most magnificent coral here.

In fact, all through our journey from the Marquesas to the Tuomotus to the Society Islands, we not only saw bleached coral, but also an enormous amount of algae, appearing to choke the life out of the reefs.

It’s a big problem throughout French Polynesia where over 420 different species of green, red, blue and brown algae grow. Among the most common is the brown algae Turbinaria ornata, which covers weakened coral like a thick blanket.

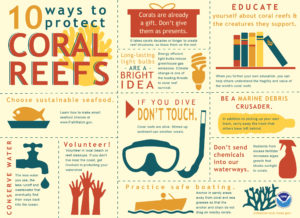

It has been an eye-opening experience that has strengthened my resolve to do what I can to help restore the coral reefs and protect this beautiful part of the world.

We’ve got work to do

As my family and friends are quick to point out, I’m an optimist by nature, especially when it comes to the environmental challenges we face today. I tend to focus on recovery. Save the hand wringing for the doubters, I say, we’ve got work to do.

I am eager to return home to share my observations, get involved with major research projects, and work on moving the dial towards better health for our oceans, including healthier coral reefs.

Changing face of coral reefs

I have vivid recollections of the sea life while diving and swimming in French Polynesia during the late 1970s. The coral was beautiful, the fish were plentiful, and watching the wavy sand corals as they attracted vibrant fish was mesmerizing.

Today’s reefs are a sad comparison. Yet, many people who go out diving today think the reefs are wonderful. I don’t think they realize that the vibrant, plentiful coral reefs of yesterday have morphed into standard stuff that is often bleached. On one level, it’s understandable as the change has been so gradual that, in many ways, it has gone unnoticed.

On another level, it’s hard to argue with numbers. Almost 20 percent of our global coral reefs are effectively lost and unlikely to recover soon, according to the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI). Another 15 percent are at a critical stage, likely to be lost in the next 10 to 20 years. Yet another 20 percent are threatened with moderate damage.

A domino effect

All these changes can have a negative domino effect as coral reefs are the home and feeding ground for about 25 percent of the ocean’s species. The Smithsonian calls corals the rainforests of the sea, but I think Sylvia Earle describes them best as “a jeweled belt around the middle of the planet.”

In search of stronger coral

So how do we make coral stronger? Earlier this year, I attended a lecture by Dr. Stephen Palumbi at Stanford University who shared a fascinating discovery. Dr. Palumbi is a professor in Marine Sciences and the Director of Hopkins Marine Station, the marine laboratory of Stanford University. He spoke about the work his team is doing on ocean corals, including the discovery of corals that appear better able to handle warmer ocean temperatures.

Dr. Palumbi’s team discovered these super corals on the island of Ofu in American Samoa, and they believe the algae associated with the corals play a role in its resilience.

Algae and corals have a symbiotic relationship: coral reefs provide algae with a structure to take root, and algae nourish coral by converting sunlight to food. But it’s all about balance, including the right type and amount of algae.

Warmer ocean temperature can upset this balance. When temperatures rise, corals spit out algae, kind of like a person taking off layers of clothes when they get hot. In doing so, they lose their food supply, turn white or bleach, and die.

Ocean acidification can also upset this balance. As the ocean continues to absorb increasing amounts of carbon dioxide, it becomes more acidic. This makes it more difficult for corals to build and maintain their calcium carbonate skeleton.

However, Dr. Palumbi’s team found that the Ofu corals are stronger, more resistant to increases ocean acidity, and the algae that they feed on are able to withstand higher water temperatures.

These are exciting discoveries, and you can bet I will be following the team’s research with great interest and optimism. In fact, I have a meeting scheduled with the folks at Stanford to see what can be done to leave this planet a better place than when I arrived.

Next stops

After our visit to Huahine, Tahiti and Moorea, Francesca and I will be flying back to California. I’m eager to see what can be done to make a difference in our beautiful oceans.

I will report back soon.

Cheers,

P.S. Don’t forget you can subscribe to our RSS feed to have blog posts delivered right to your inbox.

P.S.S. Don’t forget to check out our photos on the Society Islands and more from 40-plus years ago (Firebird Albums) and recently (Photo Album 9: Society Islands (Raiatea)). I hope you enjoy!

|

|

Sam,

I will miss your cogent and beautifully composed observations on a remote and relevant part of the world.

Peter

We have loved vicariously traveling with you. Thanks so much for the adventure!